Chapter 6: Asia Minor and Northern Iraq

- Gypsy Folk Ensemble

- Early Travelers to Greece

- Greeks & Albanians from about 1800

- Serbs, Montenegrins, Bosnians, Croatians

- Bulgarians, Macedonians

- Romanians

- The Levant

- Persia

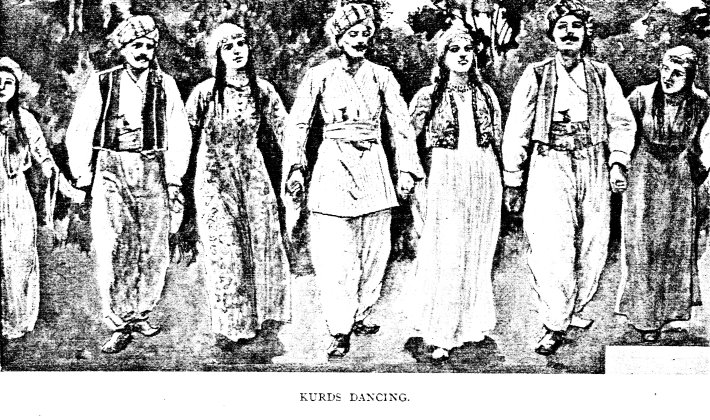

1. Kurds

Paul Lucas (1664-1737) was a French merchant and traveler. He made three voyages to the Ottoman Empire under the patronage of the French King Louis XIV from 1699 to 1717.

In 1700, traveling with a caravan in Eastern Asia Minor on the road from Malatia to Erzurum near the village of Douche (?) whose inhabitants consisted half of Turks and half of Armenians:

- Paul Lucas: Voyage du Sieur Paul Lucas au Levant, Paris, 1704, Vol. I, p. 342-343Environ une heure après que nous fûmes campez, trois Turcs dont l’un avoit une espece de hautbois, l’autre un tambour, & le troisième de petits bassins qu’il faisoit joüer entre ses droigts, vinrent danser au son de leurs instrumens devant nos tentes. L’on me dit que ces sortes de gens étoient des Curdes tous voleurs, qu’ils ne venoient ainsi que pour remarquer la force de la Caravane, & que ce seroit un grand miracle si nous n’étions pas attaquez.About an hour after we made camp, three Turks, one of which had a type of hautbois [oboe], another a drum, and the third some small basins which he played between his fingers, came to dance to the sound of their instruments before our tents. I was told that these type of people were thieving Kurds, that they only came to see how strong our caravan was, and that it would be a great miracle if we were not attacked. [They were attacked the next day]

Claudius James Rich (1787-1821), who knew several ancient and modern languages, was the resident agent for British East India Company in Bagdad. He was also involved in antiquarian research in Mesopotamia. He died of cholera in Shiraz, Persia.

In Suleimanieh (modern Sulaymaniyah in Iraq) in 1820:

Last night we were entertained by the performance of two Koordish peasants on the bilwar, or Koordish flute, made of a reed. They played in unison. The tones were soft and agreeable: the airs were melancholy, and rather monotonous. The best was a song called "Leili jan", and another beginning "Az de Naleem" *.* Besides these we were often favored with other popular Koordish airs, such as "Men Kuzha benaz"; "Mil ki Jan"; "Azeezee".

- Claudius James Rich: Narrative of a Residence in Koordistan, London, 1836, Vol. I, p. 138

In Suleimanieh on October 2, 1820:

Being informed that there was a wedding feast at a house in the outskirts of town, I determined to become a spectator of it. In order to avoid attracting attention, Mr. Bell and I put shawls about our heads, and concealed our dresses with black abbas or Arab cloaks, and, thus accoutred, we set forth at night to see the show. After a long walk we arrived at the place of the feast, an ordinary house; on the roof of which, not above six feet from the ground, we established ourselves among a great crowd of people. The courtyard, which was the scene of revelry, exhibited a crowd of Koords of every age and degree; from the gentleman, with the bush of party-coloured tassels on his head, the grim savage in goat-skin. Most of them were linked by the hand in the dance called the Tchopee, forming a ring not joined at the ends, which nearly enclosed the court-yard. These evolutions consisted in swinging to and fro with their bodies, and marking time, first with one foot, then with the other, sometimes with good heavy stamps in a way which reminded me of the Irish song, “Rising on Gad and sinking on Sugan;” while the gaiety of their hearts would occasionally manifest itself in wild shrieks. Those who did not dance filled up the intervals of the space, or covered the roof of the house which encompassed the court on four sides. Numbers squatted down in the centre of the dancers’ line, among whom were the piper and drummer. The scene was illuminated by three mashalls or torches, and the crowd bore with perfect unconcern the clouds of smoke and irruptions of sparks which poured from these flambeaus. The dancers had been at it above an hour when we arrived. After having enjoyed their exercise for about half an hour more the music ceased, and the dancers were dismised to make room for others, by a charge made upon them by the master of the house and some friends armed with sticks. When the first set had been thus ejected and the ring cleared, a stout Koord leaped into the arena and amused the company for some minutes by sundry capers and antics with a quarter-staff. The music then struck up again the notes of the Tchopee, and a string of about thirty ladies hand in hand advanced with slow and graceful step, resplendent with gold spangles, and party-coloured silks, and without even the pretext of a veil. This was really a beautiful sight, and quite a novel one to me, who had never in the East seen women, especially ladies as all of these were, so freely mixing with the men, without the slightest affectation of concealment. Even the Arab tribes women are more scrupulous.The line or string of ladies moved slowly and wavingly round the enclosure, sometimes advancing a step towards the centre, sometimes retiring, balancing their bodies and heads in a very graceful manner. The tune was soft and slow, and none of their movements were in the least abrupt or exaggerated. I was delighted with this exhitition, which lasted about half an hour. The music then ceased, and the ladies retired to their homes, first veiling themselves from head to foot, which seemed rather a superfluous precaution, as the crowd which was looking on at the dance far exceeded that which they were at any time likely to meet in the streets of Sulimania. Many of them were very fine fresh-looking women.From this exhibition it may be almost superfluous to add, that the Kurdish females in their houses are far less scrupulous than Turkish, or even Arab women. Men servants are admitted, and even from strangers they are not very cautious in concealing themselves. ...The dance is the great passion of the Koordish females. On occasion of a wedding they will volunteer their services, when not invited, and even bring small presents to the bride for permission to exhibit in the dance. On such occasions they always perform in public without any veil, however great the crowd of men may be.All the Oriental dances are of the same character, and all probably derived from the remotest antiquity. The Tchopee is a variety of the Greek Sirto, or Romeka, less animated and varied.

- Ibid, Vol. I, p. 281-287

At Bin Kudreh, a village in modern Iraq on the Diala river near the Iran border, close to Khanaqin, Iraq and Qasr-e-Shirim, Iran. In March 1820:

We arrived at Bin Kudreh, a large village belonging to Hassan Aga, a Koordish chief of Bajilan...At night he and the whole village turned out to dance the Tchopee, to the sound of the big drum and zoorna; and, to our no small amusement, they made Selim Aga [a Turkish friend of Rich] fall in with them.

- Ibid, Vol. II, p. 273

Isabella Bird (1831-1904) was a British explorer who traveled over much of the world, including Australia, Hawaii, the Rocky Mountains, Japan, Malaya, India, Tibet, China and Korea. In 1890 she was with Major Herbert Sawyer, a Military Intelligence officer in the Indian Army, who was carrying out a clandestine military survey in Kurdistan and Western Persia.

In the village of Kotchanes (modern Qodshanes in eastern Turkey north of Hakkari) with Nestorian Christians (Assyrians):

[As precursor to a wedding] there was dancing in the house late into the night, and the days were spent in feasting, sword-dances, and masquerading.

- Isabella Bird: Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan, London 1988, Vol. 2, p. 306-307 [originally published in 1891]

Men and women, of course, dance separately, and the women much in the background. The dancing, as I have seen it, is slow and stately. A number of either sex join hands in a ring, and move round to slow music, at times letting go each other’s hands for the purpose of gesticulation and waving of handkerchiefs. It is not unlike the national dance of the Bakhtiaris.

- Ibid, Vol. 2, p. 312

Walter B. Harris (1866-1933) was an English journalist for The Times who became famous for penetrating in disguise into areas of Morocco unkknown to Europeans. In the 1890s he traveled to the Middle East.

In 1895, at Benavila, a Kurdish village in northern Persia near the town of Sardasht, very close to the Turkish border:

As we were supping, the shrill sound of wooden pipes was heard, and my hosts told me that I was to witness the native dancing, a little festival having been arranged in my honour. So with a lantern we wandered to the centre of the village, where the voices and laughter of the young men and girls told us the dance was to take place.The performers had already drawn themselves up in line when I arrived, and a minute later the shrill notes of the pipe gave the signal for the dancing to commence. Some score of young men and women stood shoulder to shoulder, clasping hands, the line forming a crescent. At the given signal, the clapping of his hands by a youth who stood in front of the semi-circle of performers, the dance commenced, the entire line of men and women stepping slowly forward and then back again, each pace being taken a little to the right, so that a rotating movement was given to the string of dancers. As the music quickened so did the pace, and at each step the body from the waist upwards was bent forward and drawn back. Nor were the steps themselves the same, for the youth who gave the time ran up and down the line clapping his hands and singing and shouting out directions and changes. The principal feature of the dance seemed to be the bringing down of the right foot smartly upon the ground at intervals, when hand in hand the whole company remained with their bodies bent for a second or two, to spring back into position again at a fresh blow of the pipes. Meanwhile the slow rotating movement was maintained, so that the entire body were circling round the musicians. What laughter and fun there was! Men and girls giving themselves up to the enjoyment of their national dance, which, graceful and exhilarating, bore no trace of the sensual movements which usually mark the art of dancing in the East.

- Walter B. Harris: From Batum to Baghdad, Edinburgh, 1896, p. 216-218

Frontispiece

Ely Bannister Soane (1881-1923) was a British writer who first made his aquaintance with the Middle East as a bank clerk for the Imperial Bank of Persia at the beginning of the twentieth century. He traveled widely throughout Persia and the Kurdistan region, learning several languages. He became a stauch supporter of Kurdish independence.

At a caravanserai in Kirkuk, speaking of Haji Rasul, a Shia Moslem Kurd. In 1909:

A Kurd himself, he deplored the levity of the Kurds, who are much given to dancing and singing. Each night the Kurdish muleteers would collect on the roof of some rooms in the courtyard, and chant their interminable “Guranis” or folk songs, dancing hornpipes of ever-increasing fury and joining in roaring choruses. Sometimes they would engage in wrestling matches, and cast one another about the yard, the exercise often terminating in a display of hot temper, when knives would be drawn, to be sheathed as an onlooker made a jest that called forth laughter from all.

- E. B. Soane: To Mesopotamia & Kurdistan in Disguise, London, 1912, p. 131

2. Greeks, Armenians, Turks, and Others

Richard Chandler (1738-1810) was an English scholar educated at Oxford. Under the auspices of the Society of Dilettanti, he went on an archaeological expedition to Asia Minor and Greece in 1764-1765. In addition to his travel narratives, he also published works on his antiquarian researches.

At Lectos (Cape Baba) in the late summer of 1764 with Turks from the vicinity of Canakkale:

Our janizary, who was called Baructer Aga, played on a Turkish instrument like a guitar. Some accompanied him with their voices, singing loud. Their favourite ballad contained the praises of Stamboul or Constantinople. Two, and sometimes three or four, danced together, keeping time to a lively tune, until they were almost breathless. These extraordinary exertions were followed with a demand of bac-shish, a reward or present; which term, from its frequent use, was already become very familiar to us.

- Richard Chandler: Travels in Asia Minor 1764-1765, London, 1971, p. 26

A short time after the above near a Greek holiday outing on the European shore of the Hellespont:

It is the custom of the Greeks on these days, after fulfilling their religious duties, to indulge in festivity. Two of their musicians, seeing sitting under a shady tree, where we had dined, came and played before us, while some of our Turks danced. One of their instruments resembled a common tabour, but was larger and thicker. It was sounded with two sticks, the performer beating it with a slender one underneath, and at the same time with a bigger, which had a round knob at the end, on the top. This was accompanied by a pipe with a reed for the mouthpiece, and below it a circular rim of wood, against which the lips of the player came. His cheeks were much inflated, and the notes were so various, shrill, and disagreeable, as to remind me of a famous composition designed for the ancient aulos or flute, as was fabled, by Minerva. It was an imitation of the squalling and wailing, made by the serpent-haired gorgons, when Perseus maimed the triple sisterhood, by severing from their common body the head of Medusa.

- Ibid, p. 42-43

Dr. Hunt. In a collection of MS travels by various authors. Hunt traveled as a companion to the noted Orientalist Joseph Carlyle (1759-1804)

At the village of Boyuk Bournabashi in March, 1801 [near Bayramiç in northwest Anatolia near Troy]:

We found this town very gay and noisy on account of the celebration of a Turkish wedding, and before we retired to rest, a band of musicians, who had been brought to the wedding-feast from the Dardanelles came to our lodgings with a set of dancers. The concert was composed of three instruments not unlike clarionets, and a number of drums of different sizes. The shrillness of the pipes, and the stunning noise of the drums were ill suited to the little room in which we were sitting. Both musicians and dancers were strolling gypsies in the Turkish dress; one acted the part of clown or buffoon; and the dance was altogether so indecent, that we soon dismissed them.

- Robert Walpole: Memoirs relating to European and Asiatic Turkey, London, 1817, p. 124-125

Charles Cockerell (1788-1863) was a young (and from his writings, at times insufferable) Englishman who went to Greece to study the remains of classical architecture in preparation for a career as an architect.

At Knifnich [modern Kınık in northwestern Turkey, near Bergama] at the home of an Armenian merchant:

Finally my friend gave me a party in my honour; and in the evening, the Turkish part of the company having departed, the women, contrary to the usual Armenian custom, appeared. The music which had been sent for began to play the Greek circle, the Romaika, and we all danced it together. At the end I did what I had understood before was the height of gallantry in these countries; on passing the musicians, dancing with my fair one, I clapped a dollar into the hand of the musician to express my enjoyment. Better still, is with a bit of wax to stick your sequin on his forehead, but I had no wax even if I had wished to try it.

- Charles Robert Cockerell: Travels in Southern Europe and the Levant, 1810-1817. London, 1903, p. 140

William J. Hamilton (1805-1867) was an English geologist and member of the Geological Society of London. In 1835, he started on a geological tour of Asia Minor.

Near the city of Amasya in northern Asia Minor on August 11, 1836:

One of the women, who had some little pretensions to good looks and fine eyes, was persuaded to treat us with a song and then a dance in the true Zingani style. The song was loud, noisy, and nasal, not improved by the rude accompaniment of a most unmusical tambourine. The dances of these gipsies I had often heard described, but had never seen; they resemble those of the Spanish gitanas, and consist chiefly of a slow waltzing movement, the great merit appearing to consist in the strange and difficult contortions of the body.

-William J. Hamilton: Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus and Armenia, London, 1842, Vol. I, p. 364

James Brant was the British consul in Trebizond (1836-40), in Erzurum (1840-46) and from 1855 in Damascus. He made extensive travels in eastern Asia Minor.

On August 24, 1838 at Merek on the shores of Lake Van north of the town of Van at a “monastery dedicated to the Virgin whose festival was now being celebrated”:

Dancing seemed to be the principal amusement of the women, of whom various groups were seen treading with solemn pace the circular dance, to the sound of their usual harsh-sounding drum and fife. The women were all dressed in red cotton petticoats, with white cotton veils over their head reaching to the waist. The male portion of the assemblage were amused by the exhibition of dancing boys, or the antics of a bear.

- James Brant: “Notes of a journey through a part of Kurdistan, in the summer of 1838", Journal of the Royal Geographical Society 10, p341-434 (1840), p. 398-399

Sir Charles Fellows (1799-1860) was an English archaeologist who began his travels in Asia Minor in 1838. In a later visit, he identified several lost cities in Lydia in southern Asia Minor and shipped large quantities of sculpture to the British Museum.

At Smyrna (Izmir) in 1838:

- Sir Charles Fellows: A Journal written during an excursion in Asia Minor, London, 1839, p. 12I have several times seen the dance so well described by Mr. Lane as performed by the dancing-girls in Egypt; the dance, music, and costume are precisely the same here.

- Sir Charles Fellows: Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, London, 1852, p. 9

At the Caravan Bridge in Smyrna (Izmir) in 1838:

- A Journal ... , p. 16The Greeks also frequent this neighborhood on their gala days, and I have here on such occasions witnessed much dancing and festivity among the lower orders.

- Travels an Researches ... , p. 12

In 1840 near Kogeez in Caria (mdern Köyceğiz in the Southwestern corner of Turkey just north of the island of Rhodes):

A lute or guitar, which is found in almost every hut in this country, was soon sounded, and a youth, one of our hosts, played several airs, all extremely singular, but simple, wild, and some very harmonious. One slow melody we admired, and were told that it was a dance; the circle was enlarged, and our Cavass stood in the midst, and danced in a most singular manner the dance, as he called it, of the Yourooks or shepherds; it was accompanied with much grimace, was in slow time, and furnished a good study for attitudes. He was succeeded by a Greek, and I never was more struck than by the accurate representation of the attitudes displayed in the fauna and bacchanal figures of the antique. Mr. Scharf had, unknown to me, sketched some of them; the uplifted and curved arm, the bending head, the raised heel, and the displayed muscles -- for all the party had bare legs and feet -- exactly resembled the figures of ancient Greek sculpture. The snapping the finger, in imitation of castanets, was in admirable time to the lute accompaniment. This is not a dance for exercise or sociability, as our modern northern dances appear; it is pas seul, slow in movement, and apparently more studied then even the performance of Taglini: and whence do these tented peasants learn it? they have no schools for such accomplishments, no opera, nor any theatrical representation; but the tradition, if it may be so called, is handed down by the boys dancing for the amusement of the people at their weddings and galas. The attention and apparent quiet gratification of the whole party also formed a feature unknown to this class of people in any other nation. The musician appeared the least interested of the party, and continued his monotonous tune with mechanical precision. Each guest, whose sole attraction was a feeling of sociability, for there was no repast, nor did he expect it, lighted his torch of turpentine-wood, and retired to his tent or shed.

- Travels and Researches, p. 289-291

| ||

Frederick Burnaby (1842-1885) was an English cavalry officer. As correspondent for the London Times he traveled with General Gordon in the Sudan. He also made a journey across the Russian steppes in 1875 (described in his book Ride to Khiva, 1876). He was killed on a Nile expedition to relieve Gordon at Khartoum. His trip across Asia Minor took place in 1877.

At Yozgat, a friend of his, Vankovitch, a Polish exile from Russia residing in Yozgat, has arranged for an evening entertainment of Gypsy dancing:

Some gipsy men now entered, and, squatting down on the carpet, began to tune their lutes. One of their party carried a fearful instrument. It was rather like the bagpipes. He at once commenced a wild and discordant blast. The musicians were followed by the dancers.The chief of the gipsy women was provided with a tambourine. She was attired in a blue jacket, underneath this was a purple waistcoat, slashed with gold embroidery, a pair of very loose, yellow trousers covered her extremities. Massive gold earrings had stretched the lobes of her ears, they reached nearly to the shoulders, and by way of making herself thoroughly beautiful, and doing fit honour to the occasion, she had stained her teeth and finger-nails with some red dye. Her eyebrows had been made to meet by a line drawn with a piece of charcoal. Gold spangles were fastened to her black locks. Massive brass rings encircled her ankles, the metal jingling as she walked, or rather waddled round the room.The two girls who accompanied her were in similar costumes, but without the gold spangles for their hair, which hung in long tresses below their waists. The girls, advancing, took the hand of Vankovitch’s wife, and placed it on their heads as a sort of deferential salute. The Pole poured out a glass of raki for the fat woman, who, though a Mohammedan, was not averse to alcohol. She smacked her lips loudly; the man with the bagpipes gave vent to his feelings in a more awful sound than before; the lutes struck up in different keys, and the ball began.The two girls whirled round each other, first slowly, and then increased their pace till their long black tresses stood out at right angles from their bodies. The perspiration poured down their cheeks. The old lady, who was seated on a divan, now uncrossed her legs, beating her brass ankle-rings the one against the other, she added yet another noise to the din which prevailed. The girls snapped their castanets, and commenced wriggling their bodies around each other with such velocity that it was impossible to recognize the one from the other. All of a sudden, the music stopped. The panting dancers threw themselves down on the laps of the musicians.“What do you think of the performance?” said Vankovitch to me, as he poured out another glass of raki for the dancers. “It is real hard work, is it not?” Then, without waiting for an answer, he continued, “The Mohammedans who read of European balls, and who have never been out of Turkey, cannot understand people taking any pleasure in dancing. What is the good of it when I can hire some one else to dance for me?” is the remark.“They are not very wrong,” I here observed; “that is, if they form an idea of European dances from their own. Our Lord Chamberlain would soon put a stop to these sort of performances in England.”“The Lord Chamberlain, who is he?” inquired an Armenian who was present, and who spoke French.“He is an official who looks after public morals.”“And do you mean to say that he would object to this sort of a dance?”“Yes.”“But this is nothing,” said Vankovitch. “When there is a marriage festival in a harem, the women arrange their costumes so that one article of attire may fall off after another during the dance. The performers are finally left in very much the same garb as our first parents before the fall. We shall be spared this spectacle, for my wife is here. The gipsies will respect her presence because they know that she is a European.”Now the girls, calling upon the old woman, insisted that she too should dance. The raki had mounted into the old dame’s head. Nothing loath, she acceded to their request; rising to her feet, she commenced a pas seul in front of the engineer. First shrugging her shoulders, and then wriggling from head to toe, as if she were suffering from St. Vitus’s dance, she finally concluded by kneeling before my hostess, and making a movement as if she would kiss her feet.

- Fred Burnaby: On Horseback Through Asia Minor, London, 1877, p. 220-224

Louis Rambert (1839-1919) was a Swiss lawyer who spent more than 25 years in Constantinople, arriving in 1891 as vice-president of the company building the Salonica-Junction Railway. He was later involved with the Smyrna-Cassaba Railway Company and the administration of the Ottoman Bank, and was also Director of the Tobacco Monopoly (Regie).

At Trebizonde (moden Trabzon on the Turkish Black Sea coast) as a guest of the Vali, Kadry Bey. The Vali has gathered a group of "brigands, de jeunes sauvages hardis et audacieux" to combat contraband trade in tobacco. They are referred to as their "coldjis":

Celui-ci nous les a présentés l'autre jour dans une promenade aux environs d'Erzeroum. Il les a réunis sur une pelouse, dépendance d'un café de campagne. Nous nous sommes assis sur des escabeaux, et nos "coldjis" ont exécuté devant nous leurs danses nationales. Ils étaient là une trentaine de jeunes bandits, en cercle autour d'une grosse caisse et d'une petite flûte. Presque tout sont de beaux garçons élancés, bien découplés, à la taille souple. Grands yeux bien ouverts, nez accentué sans exagération, forte ossature de la mâchoire inférieure et du menton. Avec leur vêtement noir, presque collant, dessinant les formes de leur torse et les muscles de leurs membres développés et assouplis par l'habitude des exercises violents, coiffés de leur "couffies" noir dont les extrémités sont rejetées sur la nuque et dont les angles, ressortant à droite et à gauche de la tête, l'encadrent comme des oreilles d'éléphants, ils ont l'air de jeunes démons arrivant tout droit de l'enfer. La plupart d'entre eux ont sans doute éprouvés les rudesses des corrections du vali et les voilà dansant devant lui comme des petites filles apprivoisées. Ils se tiennent tous par la main, leur cercle s'élargit et se resserre, leurs corps se dressent de toute leur hauteur, les bras tendus au-dessus de leur tête, puis s'accroupissent dans l'attitude du chasseur à l'affût, et la grosse caisse marque le pas sans arrêt, tandis que la petite flûte remplit les airs de ses roulades ininterrompues. Après les danses d'ensemble, les artistes de la bande se livrent deux à deux à un jeu d'escrime choréographique avec des sabres à lame ondulée dont la longueur tient la milieu entre l'épée et le poignard. Ils s'attaquent en cadence, bondissent en arrière pour éviter le coup de l'adversaire, reviennent à la charge en tournoyant sur eux-mêmes. Le pas de danse est le pas oriental, court et rapide, le pied frappant le sol du talon et produisant une trépidation de tout le corps. Le vali fait venir auprès de lui un de ces jeunes grands diables auquel il adresse quelques paroles, puis il me dit: "Celui-ci a quatre ou cinq assassinats sur la conscience; quand j'ai une commission particulièrement délicate à faire exécuter, c'est lui que j'en charge. Il s'en acquitte avec adresse et sans bruit."J'espère bien que Son Excellence n'aura jamais rien à me faire dire par cet intermédiaire.

- Louis Rambert: Notes et impressions de turquie, l'empire ottoman sous Abdul Hamid II, 1895-1905, Geneva, 1926, p. 151-152

On October 25, 1904 for a ceremony at Palace (Yildiz Kiosk) in Constantinople at annual departure of caravan for Mecca:

Mais voici le cortège qui débouche en face de nous. En tête un group nombreux d'hommes qui chantent des litanies lentes et tristes. Arrivés devant la façade du palais, les chantes cessent, la colonne s'arrête et deux artistes s'avancent, le sabre au clair, et se livrent à un duel simulé, qui n'a aucun rapport avec l'escrime savante de nos professeurs d'Occident, mais qui nien est que plus pittoresque et plus émouvant. Ils bondissent comme des léopards, tournants sur eux-mêmes, s'attaquant et s'évitant avec une agilité surprenante pour s'engager dans un corps à corps assez effrayant où les coups de sabre sont lancés a toute volée, parés par de petits boucliers que chaque combattant porte au poignet gauche.

Ibid, p. 327-328

Ahmed Sabri (born about 1895) was a Turk from the town of Kemer (modern Burhaniye in western Turkey). He converted to Christianity and later resided in Athens.

We also have many interesting dances. Only the men dance in public. They are usually accompanied by music from a drum somewhat resembling an Indian tom-tom. The steps are quite intricate, and when the dancers are dressed in their festival clothes of many colors they present a beautiful sight.

- Ahmed Sabri bey: When I Was a Boy in Turkey, Boston, 1924, p. 74