Chapter 2: Greeks and Albanians From about 1800

- Gypsy Folk Ensemble

- Early Travelers to Greece

- Serbs, Montenegrins, Bosnians, Croatians

- Bulgarians, Macedonians

- Romanians

- Asia Minor & Northern Iraq

- The Levant

- Persia

1. Before the Greek War of Independence

Dr. John Sibthorp (1758-1796) succeeded his father as Professor of Botany at Oxford in 1784 and was a founder of the Linnaean Society (1788). He traveled to Greece and other areas of the Balkans on botanical collecting expeditions. He died of consumption in 1796. The following excerpt from his journal (March 1, 1795) was later published in a collection of traveler's accounts by Robert Walpole in 1820.

The scene takes place at the house of Husam Husaim, the Aga of Pyrgos in Peloponnesos who had previously promised them an Albanian dance. Husaim’s physician was from the Ionian island of Zante and Georgaki was a steward of Said Aga, chieftain of the town of Lalla, further inland from Pyrgos.

- Robert Walpole: Travels in Various Countries of the East, London, 1820, p. 78-79In the evening we went, accompanied by our fat host Georgáki, to take leave of Husam Husaim: we were courteously received, but Husam expressed his chagrin at our leaving him so abruptly. He was attended by his secretary, his physician, and a Pyrgiote. Having drank coffee and smoked our pipes, Husam introduced wine; and the dragoman taking up his guitar, the physician and the Pyrgiote, warmed by drinking, leaped up to a mimic dance. The doctor showed considerable address with his heels, and raised them sometimes so high that they reached the ears of his partner. The dance, displaying the lowest buffoonery, was applauded by the Aga, who not having the fear of Mahomet before his eyes, took large draughts of wine. A French clerk to a mercantile house at Corone, entered and joined the dance. Georgáki now pulling off his upper tunic added himself to the number, and shaking his fat sides, increased the ludicrous appearance of the groupe. The Aga thought we participated with him in the pleasure of the dance and the music, which was accompanied with Turkish songs, forcing horrid screams and hideous faces. I could not help reflecting on the barbarism and ignorance that now reigned over a country once the most enlightened; and on the difference between these sottish orgies, and the noble games that attracted the ancient states of Greece to the plains of Olympia.

J.B.S. Morritt (1772-1843): Journey through Mainia in April 1795.

Published as part of a series of travel narratives by Robert Walpole in 1817. Mainia refers to a region in the southern part of the Peloponnesus in Greece. Morritt visited several villages in the area during Easter celebrations.

The following takes place at the village of Platsa [Πλατσα] at the castle of one Capitano Christeia:

We dined with the family at twelve o’clock, and after dinner went to the great room of the castle. In it, and on the green before it, we found near a hundred people of both sexes and of all ages assembled, and partaking of the chief’s hospitality. They flocked from all the neighbouring villages, and were dancing with great vivacity. The men, during the dance, repeatedly fired their pistols through the windows, as an accompaniment to their wild gaiety; and the shouts and laughter and noise were indescribable. Among other dances, the Ariadne, mentioned in De Guy’s Travels, was introduced, and many which we had not yet seen in Greece. The men and women danced together, which was not so usual on the continent as in the islands. On my complimenting the Capitano on the performance of his lyrist, who scraped several airs on a three-stringed rebeck, here dignified with the name of λύρη, a lyre, he told me with regret, that he had indeed been fortunate enough to possess a most accomplished musician, a German, who played not only Greek dances, but many Italian and German songs; but that in 1794 his fiddler, brought up in the laxer morals of western Europe, and unmindful of the rigid principles of the Maina, had so offended by his proposals the indignant chastity of a pretty woman in the neighbourhood, that she shot him dead on the spot with a pistol.

- Robert Walpole: Memoirs relating to European and Asiatic Turkey, London, 1817, p. 52-53

The English poet George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824) traveled through Spain, Greece, Albania and Turkey in 1809 and 1810. The preface to his poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812) states that it was "begun in Albania" (in Oct/Nov 1809).

Here with a band of Albanians at Utraikey, the modern Greek town of Loutraki on the southeast coast of the Gulf of Arta in western Greece:Childe Harold's Pilgrimage - Canto IIXLVIIAnd onward did his further journey takeTo greet Albania's chief, whose dread commandIs lawless lawLVIIThe Turk, the Greek, the Albanian, and the Moor,Here mingled in their many-hued arrayLVIIIThe wild Albanian kirtled to his knee,With shawl-girt head and ornamented gun,And gold-embroider'd garments, fair to see

LXXIOn the smooth shore the night-fires brightly blazed,The feast was done, the red wine circling fast,And he that unawares had there ygazedWith gaping wonderment had stared aghast;For ere night's midmost, stillest hour was past,The native revels of the troop began;Each Palikar his sabre from him cast,And bounding hand in hand, man link'd to man,Yelling their uncouth dirge, long daunced the kirtled clan.LXXIIChilde Harold at a little distance stoodAnd view'd, but not displeased, the revelrie,Nor hated harmless mirth, however rude;In sooth, it was no vulgar sight to seeTheir barbarous, yet not indecent glee;And, as the flames along their faces gleam'd,Their gestures nimble, dark eyes flashing free,The long wild locks that to their girdles stream'd

From Notes to Childe Harold's Pilgrimage:

Dervish [one of his Albanian attendants] excelled in the dance of his country, conjectured to be a remnant of the ancient Pyrrhic; be that as it may, it is manly, and requires wonderful agility. It is very distinct from the stupid Romaika, the dull round-about of the Greeks, of which our Athenian party had so many specimens.

John Cam Hobhouse (1786-1869) was a schoolmate of Lord Byron at Cambridge and accompanied him on his travels in 1809 and 1810. He remained a lifelong friend of Byron and it was he who superintended his will and funeral upon the poet's death in 1824. He was later much involved in politics and writing and became Baron Broughton in 1851.

[The Albanian section of his trip is also found published as John Hobhouse: A Journey Through Albania, New York, 1971, a reprint based on the 1817 Philadelphia edition]

Describing the Albanians:

Although lazy in the intervals of peace, there is one amusement of which (as it reminds them of their wars, and is, in itself, a sort of friendly contest) they partake with the persevering energy and outrageous glee. I allude to their dances, which though principally resorted to after the fatigues of a march, and during their nights on the mountains, are yet occasionally their diversion on the green of their own villages.There is in them only one variety: either the hands of the party (a dozen or more in number) are locked in each other behind their backs; or every man has a handkerchief in his hand, which is held by the next to him, and so on through a long string of them. The first is a slow dance. The party stand in a semicircle; and their musicians in the middle, a fiddler and a man with a lute, continue walking from side to side, accompanying with their music the movements, which are nothing but the bending and unbending of the two ends of the semicircle, with some very slow footing, and now and then a hop.But in the handkerchief dance, which is accompanied by a song from themselves, or which is, more properly speaking, only dancing to a song, they are very violent. It is upon the leader of the string that the principal movements devolve, and all the party take this place by turns. He begins at first opening the song, and footing quietly from side to side; then he hops quickly forward dragging the whole string after him in a circle; and then twirls round, dropping frequently on his knee, and rebounding from the ground with a shout; every one repeating the burden of the song, and following the example of the leader, who, after hopping, twirling, dropping on the knee, and bounding up several times round and round, resigns his place to the man next to him. The new Coryphaeus leads them through the same evolutions, but endeavours to exceed his predecessor in the quickness and violence of his measures; and thus they continue at this sport for several hours, with very short intervals, seeming to derive fresh vigour from the words of the song, which is perhaps changed once or twice during the whole time.In order to give additional force to their vocal music, it is not unusual for two or three old men of the party to sit in the middle of the ring, and set the words of the song at the beginning of each verse, at the same time with the leader of the string; and one of them has often a lute to accompany their voices.It should have been told that this lute is a very simple instrument- a three-stringed guitar with a very long neck and a small round base, whose music is very monotonous, and which is played with what I shall be excused for calling a "plectrum", made of a piece of quill half an inch in length. The majority of the Albanians can play on this lute, which, however, is only used for, and capable of, those notes that are just sufficient for the accompaniment and marking the time of their songs.The same dance can be executed by one performer, who, in that case, does not himself sing, but dances to the voice and lute of a single musician. We saw a boy of fifteen, who, by some variation of the figure, and by the ease with which he performed the "pirouette" and the other difficult movements, made a very agreeable spectacle of this singular performance.

- Lord Broughton: Travels in Albania and other provinces of Turkey in 1809 & 1810, London, New Edition, 1858, Vol 1, p. 143-145

- John Hobhouse: A Journey Through Albania, New York, 1971, p. 135-136

At the town of Loutraki in western Greece, describing their Albanian entourage:

In the evening the gates were secured, and preparations were made for feeding our Albanians. A goat was killed, and roasted whole, and four fires were kindled in the yard, round which the soldiers seated themselves in parties. After eating and drinking, the greater part of them assembled round the largest of the fires, and, whilst ourselves and the elders of our party were seated on the ground, danced round the blaze to their own songs, in the manner before described, but with astonishing energy. All their songs were relations of some robbing exploits. One of them, which detained them more than an hour, began thus - "When we set out from Parga, there were sixty of us"; then came the burden of the verse, "Robbers all at Parga! Robbers all at Parga!" and as they roared out this stave, they whirled round the fire, dropped, and rebounded from their knees, and again whirled round, as the chorus was again repeated.

- Lord Broughton, Travels ..., Vol. 1, p. 166-167

- John Hobhouse, A Journey ..., p. 169-170

On Greek women's dancing:

Their dancing they learn without a master, from their companions. The dance, called Χορος, and, for distinction, Romaica, consists generally in slow movements, the young women holding by each other's handkerchiefs, and the leader setting the step and time, in the same manner as in the Albanian dance. The dancers themselves do not sing; but the music is a guitar, or lute, and sometimes a fiddle, accompanied by the voice of the players. When, however, men are of the party, there is a male and female alternately linked, and the performance is more animated, the party holding their handkerchiefs high over their heads, and the leader dancing through them, in a manner which, although at the time it reminded me only of our game of thread-the-needle, has been likened by some observers to the old Cretan labyrinth dance, called Geranos, or the Crane. When the amusement is to be continued throughout a night, which is often the case, the figures are various; and I have seen a young girl, at the conclusion of the dance described, jump into the middle of the room, with a tambourine in her hand, and immediately commence a pas seul, some favourite young man whom she had warned of her intention striking the strings of the guitar at the same time, and regulating the dance and music of his mistress. We once prevailed on a sprightly girl of fifteen to try the Albanian figure, and her complete success of the first attempt showed the quickness and versatility of her talents for this accomplishment.

- Lord Broughton, Travels ..., Vol. 1, p. 452

Colonel William Leake (1777-1860) was born in London and educated at the Royal Military Academy. He was sent to Constantinople by the British government to train the Turks in artillery, the Ottoman Empire being then a British ally. He surveyed large areas of Greece and Albania for the Turks in the war against Napoleon and was later the British representative at the court of the famous Ali Pasha.

This short notice is from his travels in 1809-1810, at a place just north of Ioannina in Greece on the festival of Saint John:

Some of the gayest, clothed in gorgeous dresses of Albanian lace and embroidery, were dancing the Κυκλικος Χορος in circles on the grass.

- William M. Leake: Travels in Northern Greece, London, 1835, Vol. IV, p. 88

Henry Holland, M.D., F.R.S. (1788-1873), a distant relative of Charles Darwin, obtained his medical degree at the university of Edinburgh in 1811 and then spent a year and a half traveling through Greece and the Aegean. In later life he was a successful doctor, and was physician to the royal family.

Oct. 28, 1812 at a small palace belonging to Ali Pasha at Salaora on the shore of the Gulf of Arta:

In the evening we were drawn by the sound of music, to one of the furnished apartments at the other end of the palace; we found there a singular troupe of people, two or three Jews who had just arrived from Ioannina, some Albanian officers, and ten or twelve soldiers and attendants of the same nation. We learnt that the Jews were persons employed in furnishing the palaces of Ali Pasha, and that they were now on their way to Prevesa, to prepare for the reception of the Vizier, who was expected there in the course of a few weeks. They invited us to enter the apartment, and we seated ourselves on the divans beside them. Wine, impregnated with turpentine, as is the custom in every part of continental Greece, was handed to us by an Albanian soldier, and succeeded by coffee and Turkish pipes. Mean-while the music, which had been arrested for a short time by our entrance, was again resumed. The national airs of Albania were sung by two natives, accompanied by the violin, the pipe, and tambourine; the songs, which were chiefly of a martial nature, were often delivered in a sort of alternate response by the two voices, and in a style of music bearing the mixed character of simplicity and wildness. The pipe which was extremely shrill and harsh, appeared to regulate the pauses of the voice; and upon these pauses, which were very long and accurately measured, much of the harmony seemed todepend. The cadence, too, was singularly lengthened in these airs, and its frequent occurrence at each one of the pauses gave great additional wildness to the music. An Albanese dance followed, exceeding in strange uncouthness what might be expected from a North American savage: it was performed by a single person, the pipe and tambourine accompanying his movements. He threw back his long hair in wild disorder, closed his eyes, and unceasingly for ten minutes went through all the most violent and unnatural postures; sometimes strongly contorting his body to one side, then throwing himself on his knees for a few seconds; sometimes whirling rapidly round, at other times again casting his arms violently about his head. If at any moment his efforts appeared to languish, the increasing loudness of the pipe summoned him to fresh exertion, and he did not cease till apparently exhausted by fatigue. When the entertainment was over, the musicians and dancer followed us to our apartment, to seek some recompense for their labours.This national dance of the Albanians, the Albanitiko as it is generally called, is very often performed by two persons; I will not pretend to say how far it resembles, or is derived from, the ancient Pyrrhic, but the suggestion of its similarity could not fail to occur, in observing the strange and outrageous contortions which form the peculiar character of this entertainment.

- Henry Holland: Travels in the Ionian Isles, Albania, Thessaly, Macedonia, &c, during the years 1812 and 1813, London, 1815 (Reprint New York, 1971), p. 79-80

In a description of the life and customs of the Greeks of Ioannina:

The national and pleasing dance of the Romaika, appears to be less common in Albania than in the Morea and other parts of Greece; perhaps an effect of the more frequent use of the Albanitiko, or Albanian dance, in this part of the country. There is an extreme difference in the character of the two dances; the latter, wild, uncouth, and abounding in strange gestures; the Romaika, graceful, though sometimes lively, and well fitted to display the beauty of attitude in the human form. Both are supposed to have been derived, with more or less of change, from the ancient times of Greece; and the claim of the Romaika in particular to a classical origin appears to have some reality. Its history has been connected with the dance invented at Delos, when Theseus came hither from Crete, to commemorate the adventure of Ariadne and the Cretan Labyrinth; and the character of its movements has much correspondence with those described by Plutarch, in his life of Theseus. The Ariadne of the dance is selected either in rotation, or from some habitual deference to youth and beauty. She holds in her left hand a white handkerchief, the clue to Theseus, who follows next in the dance; having the other end of the handkerchief in his right hand, and giving his left to a second female. The alternation of the sexes, hand in hand, then goes on to any number. The chief action of the dance then devolves upon the two leaders, the others merely following their movements, generally in a sort of circular outline, and with a step alternately advancing and receding to the measures of the music. The leading female, with an action of the arms and figure directed by her own choice, conducts her lover, as he may be supposed, in a winding and labyrinthine course, each of them constantly varying their movements, partly in obedience to the music, which is either slow and measured, or more lively and impetuous; partly from the spirit of the moment, and the suggestion of their own taste. This rapid and frequent change of figure, together with the power of giving expression and creating novelty, renders the Romaika a very pleasing dance; and perhaps among the best of those which have become national, since the plan of its movement allows scope both to the learned and unlearned in the art. In a ball-room at Athens, I have seen it performed with great effect. Still more I have enjoyed its exhibition in some Arcadian villages; where in the spring of the year, and when the whole country was glowing with beauty, groupes of youth of both sexes were assembled amidst their habitations, circling round in the mazes of this dance; with flowing hair, and a dress picturesque enough, even for the outline which fancy frames of Arcadian scenery. It is impossible to look upon the Romaika without the suggestion of antiquity; as well as in the representation we have upon marbles and vases, as in the description of similar movements by the poets of that age.

- Ibid, p. 167-168

Ali Pasha visiting the house of a leading Greek citizen of Ioannina:

The Vizier eats and sits alone, the rest of the company standing at a distance; but the master and mistress of the house are generally invited to take seats near him. Music and dancing are in most cases provided for his entertainment. The music is Turkish or Albanese, performed with tabors, guitars, and the tambourine, and often accompanied by the wild songs of the country: the dances also in general Albanese, and performed by youth of both sexes, dressed with all the richness that belongs to the national costume.

- Ibid, p. 189

At a ball in Athens given by an English resident of Athens, the Honourable Frederic North, in January of 1813:

The ball in questiion was attended by more than 90 Athenians, among whom were between thirty and forty ladies, all habited in the Greek fashion, and many of them with great richness of decoration. The dance of the Romaika, which I have elsewhere described, occupied the greater part of the evening; mixed at intervals with the Albanitiko; which was here refined into somewhat less of wildness, than belongs to the native dance.

- Ibid, p. 415

Charles Cockerell (1788-1863) was a young (and from his writings, at times insufferable) Englishman who went to Greece to study the remains of classical architecture in preparation for a career as an architect.

In Athens with two friends:

March 13 is the Turkish New Year’s Day, and is a great festival with them. The women go out to Asomatos and dance on the grass. Men are not admitted to the party, but Greek women are. Linckh, Haller and I went to see them from a distance, taking with us a glass, the better to see them. We were discovered, and some Turkish boys, many of whom were armed, came in great force towards us, and began to throw stones at us from some way off.

- Charles Robert Cockerell: Travels in Southern Europe and the Levant, 1810-1817, London, 1903, p. 47

At the island of Aegina with Greek workmen at an excavation. Cockerell stopped the men from dancing and told them to get back to work:

One of them produced a fiddle; they settled into a ring and were preparing to dance.

- Ibid, p. 53

At Aegina at dinner with a Turkish official:

We finished the evening with the Albanian dance.

- Ibid, p. 56

Reverend Thomas Hughes (1786-1847) visited Ali Pasha in Janina (Ioannina) while traveling as the tutor of Richard Townley Parker in 1813. They traveled for a while to Albania with Charles Cockerell (see above) who refers to Hughes as “bearleading” Mr Parker in Athens. Shortly after Cockerell left their party, they were invited to the wedding of Giovanni Melas, a young Greek merchant in the town of Ioannina:

We were much more pleased with the next species of entertainment, which consisted of the Albanitico, or national dance of the Albanian palikars, performed by several of the most skillful among the vizir’s guards who had been invited to the feast. The evolutions and figures of this exercise served to display the astonishing activity and muscular strength of these hardy mountaineers, who grasping each other lightly by the hands, moved for a time slowly backwards and forwards, then hurried round in a quick circular movement according to the excitement of the music and their own voices, whilt the coryphaeus or leader, who was frequently changed, made surprising leaps, bending backward till his head almost touched the ground, and then starting up into the air with the elastic spring of a bow, whilst his long hair flowed in wild confusion over his shoulders*. After this was finished, the bridegroom with several of his guests imitated their example, with less agility, but with much more grace and elegance. Dancing is still considered by the moderns as it was by the ancient Greeks, a requisite accomplishment in the composition of a gentleman.

- Thomas Smart Hughes: Travels in Sicily, Greece and Albania, London, 1820, Vol. 2, p. 31-32

Charles Pertusier (1779-1836) was a French artillery officer and embassy attaché in Constantinople. He made a military assessment of Bosnia.

Speaking in contrast to the quiet of the Bosnian Moslem villages:

- Charles Pertusier: La Bosnie considérée dans ses rapports avec L'Empire Ottoman, Paris, 1822, p. 309Les villages grecs, où l'oppresion n'est pas en sentinelle, sont bien plus animés. On conduit la charrue en chantant; les jours de fête la jeunesse des deux sexes se réunit sous la platane du hameau pour danser la romeca.The Greek villages, where oppression is not so severe, are much more lively. They sing while plowing; on feast days the youth of both sexes gather under the village's Plane tree to dance the romeca.

2. During and After the Greek War of Independence

[The Greek War of Independence from 1821 to 1832 led to the establishment of an independent Kingdom of Greece with Prince Otto of Bavaria installed as the new king. Travelers from the West, especially Victorian era Englishmen, become more frequent after this time.]

David Urquhart (1805-1877) was born in Scotland but educated in Europe. He traveled to Greece to support the Greeks in their War of Independence (1821-1832) against the Ottoman Empire and served on the commission which defined the border for the new Greek state.

With Greek soldiers on the shore of the Gulf of Arta:

When the evening had set in, and the moon arose, the long Romaika was led out on the mountain’s brow.

“Their leader sung, and bounded to his song,With choral voice and step, the martial throng.”

For two long hours did the leaders dip and twirl, while the long tail ebbed and flowed, like a following wave, to the mellifluous air—

Πϖϛ τὸ τϱίβουν, τὸ πὶπὲϱι῎Οι διαβὸλοι ϰαλογἓϱοι.

- David Urquhart: The Spirit of the East, London, 1839 (2nd edition), Vol. I, p. 127-128

At the village of Cardia (modern Καρδια), about 20 miles south of Salonika (Thessaloniki):

Soon after leaving Cardia, as we turned the crest of a hill, we suddenly came on a group of nine peasants in a circle, locked arm-in-arm, and dancing, or rather leaping together, to the sound of a bagpipe, the musician standing in the centre. On this landscape, which looked so like a study of the old Florentine school, these gaily attired peasantry dancing on the hill-side seemed a group of Perugino’s Muses, just leapt from the canvass.

- Ibid, Vol. II, p. 64-65

Some 7 or 8 miles from the village of Ravanikia, near village of Gomati (modern Γοματι), in Chalcidice near Mount Athos, he met with a monk and they used a fallen tree for a campfire:

As the night darkened, the burning tree became a very beautiful and exhilarating object; and when at length it fell with a crash, and rolled downwards for many yards, supporting itslf on its reversed and flaming limbs, my guards leaped up in ecstasy, and discharged their muskets and their pistols, and called aloud for Romaika, which the sprightly monk did not disdain to lead.

- Ibid, Vol. II, p. 130

At village of Gomati at the house of a woman worried about her husband:

She sat crouching in a corner, and when I attempted to say something encouraging to her, she replied, “Go see the fine cow I am going to sell, to buy a handkerchief, that my husband and I may dance together!”*

* In dancing, they hold the ends of a handkerchief; the sense implied, is destitution and wretchedness.

- Ibid, Vol. II, p. 133

Having an attack of ague, he was detained several days at Ozeros (modern Ierissos - Ίερισσοσ just north of Mt Athos) convalescing:

I ought not to omit the kindness of the Aga, a negro, who, during four days that I was detained here, came daily to inquire for me, and always drew something out which he had concealed in his sleeve: one day it was a water-melon; another day it was a fowl; “for,” said he, “you are weak, and want something to strengthen you.” I was at one time able to go and sit before the door, and he immediately bethought himself of amusing me by making the peasants dance. They had little will for dancing; but, before I was aware of it , a score of them were brought from their vintage and ordered to dance: “What could they do?” said the Primate, “dancing is Angaria (corvée) like anything else.”

- Ibid, Vol. II, p. 195

Robert Pashley (1805-1859), after taking his MA at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1832, went on a journey to Greece, Crete and Asia Minor. In 1834 he was at the village of Rhogdhiá (modern Ρογδια or Ροδια in the north of the island of Crete, west of Iraklion). Manias was his guide and a native of Sfakia.

Before eleven o’clock these sports were abandoned, and the dance and its accompanying song were commenced. The cyclic chorus exhibited consisted of six women and as many men, each of whom held the hand of his neighbor. The coryphaeus favoured us by singing various poetical effusions as they danced.It requires no great imaginative power to regard the dance of these Cretan youths and women, as an image, which still preserves some of the chief features of the Cnossian chorus of three thousand years ago. As songs are now sung by the peasants on these occasions, so, in ancient times, there was a hyporchem, or ballad, with which the Cretans, more than all other Greeks, delighted to accompany their motions in the dance.The little songs thus sung, at the present day, are called Madhinádhas by the Cretans: I collected many of these during my stay in the island.

- Robert Pashley: Travels in Crete, London, 1837 (Reprinted Amsterdam, 1970), Vol. 1, p. 245-246

It must, however, be observed that no woman of the island ever sings: and the Sfakian women, whose seclusion and reserve is greater than that of the other female Cretans, never even dance, except on some great religious festivals, and then only with very near relations. Maniás, who thinks that the readiness, with which the women of Mylopótamo and other parts of the island join in the dance, is hardly creditable to them, was greatly horrified at the idea of any respectable female’s ever singing; and assured me that it was quite impossible for a Greek woman to disgrace herself by doing anything so disreputable.

-Ibid, Vol. 1, p. 255-256

William J. Hamilton (1805-1867) was an English geologist and member of the Geological Society of London. In 1835, he started on a geological tour of Asia Minor.

At the village of Malona on Rhodes, January, 29, 1837:

The whole population of Malona had turned out to witness the festivities in honour of a marriage. These consisted almost entirely of dancing and drinking: in the former the company danced in a ring, to the sound of a lugubrious bagpipe, encircling the more honoured of the guests.

- William J. Hamilton: Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus and Armenia, London, 1842, Vol. 2, p. 52

Edward Lear (1812-1888) has become famous for his nonsense rhymes for children, but he was a talented artist as well. For reasons of health he spent much time in the Mediterranean area and in 1848-49 he explored Greece, the Ionian islands, Egypt and the wildest reaches of Albania, making many sketches along the way.

At the rock of Zalongo, above village of Kamarina, just East of Preveza, May 1849. Ali's attack had occurred at the end of 1803:

This was the scene of one of those terrible tragedies so frequent during the Suliote war with Ali. At its summit twenty-two women of Suli took refuge after the capture of their rock by the Mohammedans, and with their children awaited the issue of a desperate combat between their husbands and brothers, and the soldiers of the Vizir of Yannina. Their cause was lost; but as the enemy scaled the rock to take the women prisoners, they dashed all their children on the crags below, and joining their hands, while they sang the songs of their own dear land, they advanced nearer and nearer to the edge of the precipice, when from the brink a victim precipitated herself into the deep below at each recurring round of the dance, until all were destroyed. When the foe arrived at the summit the heroic Suliotes were beyond his reach.

Edward Lear: Journals of a Landscape Painter in Greece And Albania, London, 1851 (Reprinted 1988), p. 182-183

At the village of Nomi about 4 hours east of Trikala in May 1849. The modern Thessalian village is on the Pinios river banks 10 miles east of Trikala:

All the village was alive with the gaieties of a wedding. Like the dance L___ and I had seen at Arachova, the women joined hand-in-hand, measuredly footing it in a large semicircle, to a minor cadence played on two pipes; their dresses were most beautiful.

- Ibid, p. 219

Eustace C. Grenville Murray (1824-1881), a natural son of the Duke of Buckingham, seems to have made a career out of getting himself into trouble. He was dismissed from his foreign office job at Vienna for moonlighting as a newspaper correspondent, and was later horsewhipped by an irate Lord for a libel published in a newspaper he founded in London. For denying his authorship of the article, he was convicted of perjury but escaped to the continent and spent the rest of his life as an exile, acting as a correspondent for London papers. In between troubles he was for a period attached to the British embassy in Constantinople.

At Greek Easter at Constantinople:

The men dance together their uncouth national dances, to a rude and inharmonious music: it is the same dance that may have been danced by the companions of Leonidas and Miltiades, or in the ancient chorus; the dance we see pictured on old vases, and in the silent chambers of Pompeii. Some ten or twelve men, of ages between twenty and fifty-five, take each other by the hand, and form themselves into a semicircle; they then begin to stamp their feet slowly, and to excite themselves till the measured stamp becomes a frantic jump, the song a howl. They are headed by a dancing-master, who twirls a handkerchief, and directs their movements. One by one, as the dancers retire from sheer prostration, their places are filled up by others; and sometimes we saw some sunburnt old fellow look bashful as a maiden when asked to join the party; but he always ended by giving his consent at last, and would come scuffling along, blushing and smirking, till he warmed to the fun, after which he jumped away as lustily as the rest. I could have wished the dancers had not been so dirty and down-at-heel as they were, and I could have dispensed with the presence of a fat old lady in a great coat, and having her head bound up from the face-ache, who came to inspect the proceedings; but in spite of these drawbacks, the scene was curious and interesting.

- Eustace C. Grenville Murray: The Roving Englishman in Turkey; being sketches from life, London, 1855, p. 104

At the Feast of St. Demetrius, Nov. 7, at the village of Moria on the island of Mytilene or Lesbos near the capital city of Mytilene:

As far as the dances, I regret to be obliged to assure the antiquaries that they are very awkward clumsy hops when actually performed. Let him fancy half a dozen heavy louts, aged between twenty-five and fifty- eight, hopping about and bumping against each other with senseless gestures, while the last man endeavours to win some burly by-stander (aged forty-two) to make a goose of himself in the same way.

- Ibid, p. 147

Henry Fanshawe Tozer (1829-1916) was an English geographer who traveled in Greece and Asia Minor. Here he is at the village of Zagora near Mount Pelion in Thessaly:

In the evening we went to see the dancing, which had been kept up, to the sound of a drum and two clarionets, ever since the morning service. The scene of it was an open space behind the church, with a circular paved area, like that of a threshing floor. The accessaries of this were admirably picturesque: all round it rose enormous plane-trees, and in front was a view of the sea and islands in contrast with the cupola of the church and one grand tapering cypress, while behind, where the ground is steep, the women were arranged all together on the slopes in a semicircle, like the spectators in an ancient theatre. The men stood round the area, and the whole assemblage was very large, multitudes having come by sea from the villages of Pelion for a long way round. It was consequently an excellent opportunity for studying the physiognomy of the people of the district: many of the men were tall of stature, and a few of the women were good looking, but the Bulgarian cast of face decidedly predominated amongst them, though a fair number had Greek features, and the dark Greek eye was far the most common. The dresses were unusually commonplace, as the men wore the dark-coloured baggy Hydriote trowsers; in fact, the only thing worth noticing in the whole multitude was the effect produced by the large number of crimson fezes. The performance, too, was disappointing; I never saw the Romaika worse danced: on this occasion it quite deserved the name Byron gives it of “a dull roundabout,” which certainly is not applicable to it as it is performed in parts of the Morea, where a graceful serpentine movement is often introduced, and the hands of those who join in it are linked very elegantly. As a national dance, however, there is always this to be said for it, that it has the advantage of being easy, and of allowing a large number to take part. The company is formed into a ring, broken at one point, with the ends overlapping, so as to admit of indefinite extension, even to the formation of an inner coil; a step or two forward, and then a step or two backward, followed by one to the side, keeps the whole ring in movement and circulating. The largest number we saw dancing together was six-and-thirty; of these but few were women, and those of that sex who did join, performed their part in a most business-like manner, and with a sobriety of deportment worthy of a very solemn function indeed. A few of the non-residents in Frank costume took part, the most conspicuous among them being an old gentleman in a hat three sizes too big for him, and wearing a general appearance of seediness, as if he had lately turned out from Holywell Street: he danced most vigorously. For some time our host, the doctor, led the dance, which he did with grace and dignity. The men seemed thoroughly to enjoy it, and relinquished the scene unwillingly at nightfall.

- Henry Tozer (1829-1916): Researches in the Highlands of Turkey, London, 1869, p. 118-119

Wadham Peacock, educated at Cambridge, was secretary to Sir William Kirby Greene, the British Consul General in the north Albanian city of Shkodra, in the 1880s. He later published a book about the country.

The following took place at an Orthodox wedding in Shkodra:

after supper ... the Albanian wedding dance was performed. The men and women formed up in two lines opposite one another in the balcony, with their arms around each other's necks, and first the line of men danced slowly forward to meet the women, singing the monotonous marriage hymn. As the men retired the women danced forward after them singing the next verse, and so the two lines continued swaying backwards and forwards, chanting their epithalium for half an hour.

- Wadham Peacock: Albania, the foundling state of Europe, New York, 1914, p. 74

James Rennell Rodd (1858-1941), a career diplomat with an Oxford education, was the British Attaché in Berlin from 1884-88, after which he went to Athens in 1888 as second secretary to the legation, and then 3 years later moved on to Rome. He played an important part in Italy’s decision to join the allies in the First World War. He became Baron Rennell in 1933.

Describing events at the Paneguris or festivals for a saint’s day:

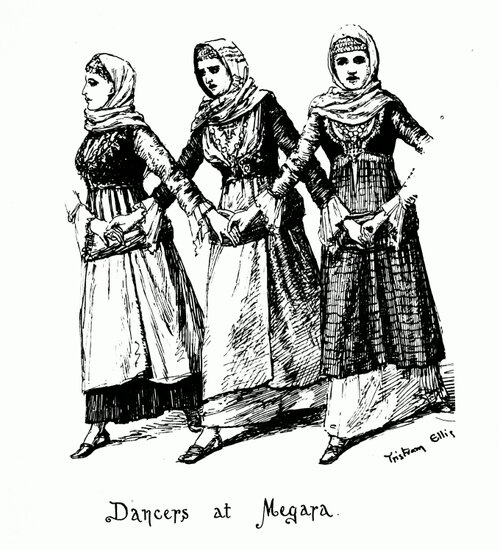

The dancing of the peasants is somewhat solemn, and well befits the semi-religious character of these occasions. There is little abandonment to the hilarity of motion, apparently little sensuous pleasure in the common rhythmic step; but the suggestion is ever recurring that some unconscious tradition of an ancient sacred significance preserves the decorum of the dancers. It has even been maintained that in the various local figure-dances traces of some former pantomimic action may be detected; and as each dance in the different localities has its own particular song of accompaniment, this has, perhaps, replaced the narrative or dramatic part, while the dance has taken the place of the mimic representation.Four principal forms may be distinguished among the many varieties of the popular dance. That called the Levéntikos (From Λεβέντης, nimble or quick) is executed either by two men or two women, who stand side by side, a pace or two apart, looking straight in front of them. They move forward and backward, springing up and round, making long turns, and then coming back to the original position, each following the movements of the other, but always dancing apart. The men frequently accompany their steps with clapping of hands.The Syrtos, a word signifying “drawn along,” is danced by men and women in a line; but where there are male dancers the leader is always a man. He holds with his or her left hand the right of the next dancer. The chain winds round and round rather solemnly; now one foot is lifted, now the other; and the bodies swing inwards or outwards together, according to the rhythm of the dancing song, or pipes and drum.The Clistos (Κλειστὸς = closed) differs from the Syrtos only in the manner in which the chain is linked. The leader has the right hand free, and holds with the left the arm of the second dancer. The second, with his right hand, holds the right hand of the third, and with his left the right hand of the fourth, and so hands are linked across each alternate dancer along the whole line.The Tsiámikos is a dance in which the leader of the line does all the dancing; the rest, who are linked to him by a handkerchief held in his left hand, only follow and keep time, generally singing in accompaniment a martial air. When the leader gets tired, he drops to the end of the line, and the second in order succeeds his. The leader, who often waves a handkerchief in his free right hand, follows the measure of the pipes or the song, moving alternately fast or slow, leaping into the air, then at regular intervals passing under his own and his companion’s linked hands, and occasionally enlivening the step by falling forward on the knee and springing up with a rebound from the floor. The great art consists in throwing the head as far back as possible without losing balance, and in this the second dancer supports him. Sometimes even, to show his suppleness and agility, he will place a glass of water on his forehead and dance a round without spilling its contents. This is the favourite dance of the soldiers, and they may often be seen engaged in it when the word is given to fall out in the intervals of the drill. It is also danced by the Albanians, and its name would seem to imply that it owes its origin to the Tzamé or Schumik tribes.Of these dances, and especially of the last, there are numberless variations, and each one has its distinctive name; such are the Siganòs, Pediktòs, Soústa, Ankaliastòs, the Tservòs, probably of Sclavonic origin, and the Syndetòs, and Gonatistòs, which are favourite dances in the islands. In these last the dancers advance with two or three forward steps to the right and one to the left, then retire again, and wind round to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument called the lyra. The differences between these various dances are all well defined, and they are looked upon as quite distinct; but the general effect produced is much the same in all.In Rhodes there is yet another method of forming the line. The girl immediately behind the leader, who will generally be her future bridegroom, holds fast by his girdle with her right hand. His right is free, holding the handkerchief which he waves, and with his left he takes the right hand of the third in line, the second being linked to the fourth, and so on. On ancient vases discovered in the island a dance extremely similar to this Rhoditikòs is found represented.The famous dances at Megara, which are held on Easter Tuesday, and on every subsequent feast-day until the day of St. George (April 23, O.S.), are more elaborate in character. The dances above described may be seen there; but it is the dance of the women known as the Tratta, a word of Italian origin, but similar in etymology to Syrtos, which has excited so much curiosity. In the morning it may be seen outside the town on a little plateau of hills among the trees, and in the afternoon in the central square of the town. On these occasions the whole population gathers at the dancing place, while numbers of spectators flock in from Athens, Corinth, and all the neigbourhood.It has been suggested, and with much probability, that this dance, as well as the Syrtos, is a rhythmic adaptation of the familiar action of drawing in the seine net. A row is formed of some twenty women, each linking her hands to the right and left across her immediate neighbour’s to those of the dancer next but one; so that here also, as in the Clistos, the line is joined together by a chain of crossing arms. The married women dance together, the unmarried women form other chains, and a particularly pretty feature in the festival are the lines of dancing children. The movement is by the right, and the leader, who with her left hand holds the right of the third dancer, and with her right the right of her neighbour, has to draw the whole line along; the work is very hard, and they often grow tired out under the hot spring sun. There is plenty of rude music of pipes, drums, and fiddles in the square; but these are chiefly engaged in playing the accompaniments of the men who are dancing the handkerchief dance, while the girls and women move to a kind of low twittering song of their own, in time with the step, which sounds like the note of a large company of swallows. The body is turned to the right, and the line advances obliquely with four long rapid steps, all the feet moving together with perfect precision, the points of their red slippers coming rhythmically forward, and all the bodies swinging as one. After the four advancing steps follow three shorter ones backward, and then the line winds round like a snake, always moving by the right, with a moments pause as the leader and the last dancer stand back to back. The step appears to be extremely simple, not to say monotonous, and yet the precision with which it is accomplished, the simultaneousness of every movement, cannot be easy to acquire; while the general effect of these serpentining chains of linked figures, in their bright dresses and floating veils, advancing, retiring, and winding round, is particularly graceful and pretty. Throughout there is no confusion nor noise; a sense of moderation and restraint prevails. It is a sight not easily forgotten this village festival—for Megara, though it covers a large area, is scarcely more than a big village—the blaze of colour in the skirts and aprons of the women, the red caps and clean white kilts of the men, the universal participation, the refined and pretty features of the young girls, the handsome bronzed faces of the pallikars—and all this in a wonderful setting of mountain, sea, and isles, under the April sun of Greece.The peasant’s dance leads on by a natural sequence to the consideration of the peasant marriage, for not only is dancing one of the characteristic features of wedding festivities, but it is also on the dancing ground, where all the villagers assemble to make holiday, that marriages are most commonly arranged...

- Rennell Rodd: The Customs and Lore of Modern Greece, London, 1892, p. 85-90

Frontispiece

Clive Bigham (1872-1956), later Viscount Mersey, covered the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 for the London Times traveling with the Turkish army. The episode described below took place before the start of the war, at the Milona Pass separating Greece and Turkey, near the town of Elassona. The Turkish Albanian soldiers sometimes went to visit their Greek counterparts at their border blockhouse.

Often we watched the troops exercising in the plain below, or, what was much more interesting, the Euzonoi and Albanians dancing opposition dances round their blockhouses, hand in hand, to the accompaniment of a reed pipe.

- Clive Bigham: With the Turkish Army in Thessaly, London, 1897, p. 35

Lucy Mary Jane Garnett (1849-1934) was a traveler and writer who published a number of works on life in the Balkans. Here she describes a picture of Sunday village life among Macedonian Greeks:

In the afternoon the peasants resort en masse to the village green. The middle-aged and elderly men take their places in the background under the rustic vine-embowered verandah of the coffee-house, the matrons, with their little ones, gather under the trees to gossip, while their elder sons and daughters perform the syrto, the "long-drawn" classic dance. Each youth produces his handkerchief, which he holds by one corner, presenting the other to his partner; she in turn extends her own to the dancer next to her, and, the line thus formed, "Romaika's dull round" is danced to the rhythm of a song chanted in dialog form, with or without the accompaniment of pipe and viol, until the lengthening shadows of evening send the villagers home to their sunset meal.

- Lucy M. J. Garnett: Turkish Life in Town and Country, New York, 1904, p. 242

Philip Sanford Marden (1874-1963) was editor of the Lowell (MA) Courier-Citizen from 1902 to 1941. He was the author of several travel books; this was his first.

In Canea, Crete:

From a neighboring coffeehouse there will be heard to trickle a wild and barbaric melody tortured out of a long-suffering fiddle that cannot, by any stretch of euphemism, be called a violin; or men may be seen dancing in a sedate and solemn circle, arms spread on each other's shoulders in the Greek fashion, to the minor cadences of the plaintive "bouzouki", or Greek guitar.

- Philip Sanford Marden: Greece and the Aegean Islands, Boston, 1907, p. 25

At a festival in Menidi, at the time a large village of about 3500 inhabitants and now the Athens suburb of Aharnes, one day after Easter:

...less extensive than the annual Easter dances at Megara, but still of the same general type ... It may be that these dances are direct descendants of ancient rites, like so many of the features of the present Orthodox church; but whatever their significance and history, they certainly present the best opportunity to see the peasantry of the district in their richest gala array, which is something almost too gorgeous to describe. ... Outside, the square was thronged with merry-makers, some dancing in the solemn Greek fashion, in a circle with arms extended on each others' shoulders, moving slowly around and around to the monotonous wail of a clarionet. ... The dance was held on a broad level space, just east of the town, about which a crowd had already gathered. We were escorted thither and duly presented to the demarch, or mayor, who bestowed upon us the freedom of the city and the hospitality of his own home if we required it. He was a handsome man, dressed in a black cut-away coat and other garments of a decidedly civilized nature, which seemed curiosly incongruous in those surroundings, as indeed did his own face, which was pronouncedly Hibernian and won for him the sobriquet of "O'Sullivan" on the spot. His stay with us was brief, for the dance was to begin, and nothing would do but the mayor should lead the first two rounds. This he did with much grace, though we were told that he did not relish the task, and only did it because if he balked the votes at the next election would go to some other aspirant. The dance was simple enough, being a mere solemn circling around of a long procession of those gorgeous maidens, numbering perhaps a hundred or more, hand in hand and keeping time to the music of a quaint band composed of drum, clarionet, and a sort of penny whistle. The demarch danced best of all, and after two stately rounds of the green inclosure left the circle and watched the show at his leisure, his face beaming with the sweet consciousness of political security and duty faithfully performed.

- Ibid, p.139-144

Edith Durham (1863-1944) was an English artist who made her first trip to the Balkans in about 1900 and continued traveled throughout the area for the next twenty years. Her particular specialty was Albania where she was held in high regard.

A remarkable characteristic of all the mountain tribes is that they have almost no amusements; games I asked for vainly, and I never saw a dance but once. The singing of the national ballads is the only pastime.

- M. Edith Durham: High Albania, London, 1909, p. 171

Celebrating the Constitution of 1908 and a release of prisoners. The Shala were a northern Albanian tribe:

Shala then started a wondrous dance, the only mountain dance I have seen. Four men pranced grotesquely, stepping high and waving their arms, yelling the while, but unaccompanied with any music. One old boy, in a crimson djemadan, had lost one arm and brandished a sword with the other to make up.

- Ibid, p. 229

"GREECE" in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th edition, New York, 1910/11

Among the popular amusements of the Greeks dancing holds a prominent place; the dance is of various kinds; the most usual is the somewhat inanimate round dance (συρτό or τράτα), in which a number of persons, usually of the same sex, take part in holding hands; it seems identical with the Slavonic kolo ("circle"). The more lively Albanian fling is generally danced by three or four persons, one of whom executes a series of leaps and pirouettes. The national music is primitive and monotonous.

[The article was written by James David Bourchier (1850-1920) who was a corrrespondent for The Times of London in the Balkans from 1888 to 1918 and who became a major figure in Balkan politics, especially in Bulgaria]